When I knocked on the door of the Jewish Cemetery in Ferrara I didn’t really know what to expect. I’d read Giorgio Bassani’s novel ‘The Garden of the Finzi Contini’ from cover to cover – several times. I felt compelled to visit this small city, south of Venice and see for myself what remains of the pre-war world that Bassani wrote about so eloquently.

The elderly lady who shuffled to the door looked me up and down with a critical eye. I could hear her brain working. Foreign, alone, pale, possibly from Ireland or maybe Holland she was thinking. She ushered me into the hall and through a second door into the garden. Bassani’s down there she said gesturing vaguely with an arthritic hand. Walk down the path to your right, to the end, beyond the tomatoes. You’ll see him close to the wall.

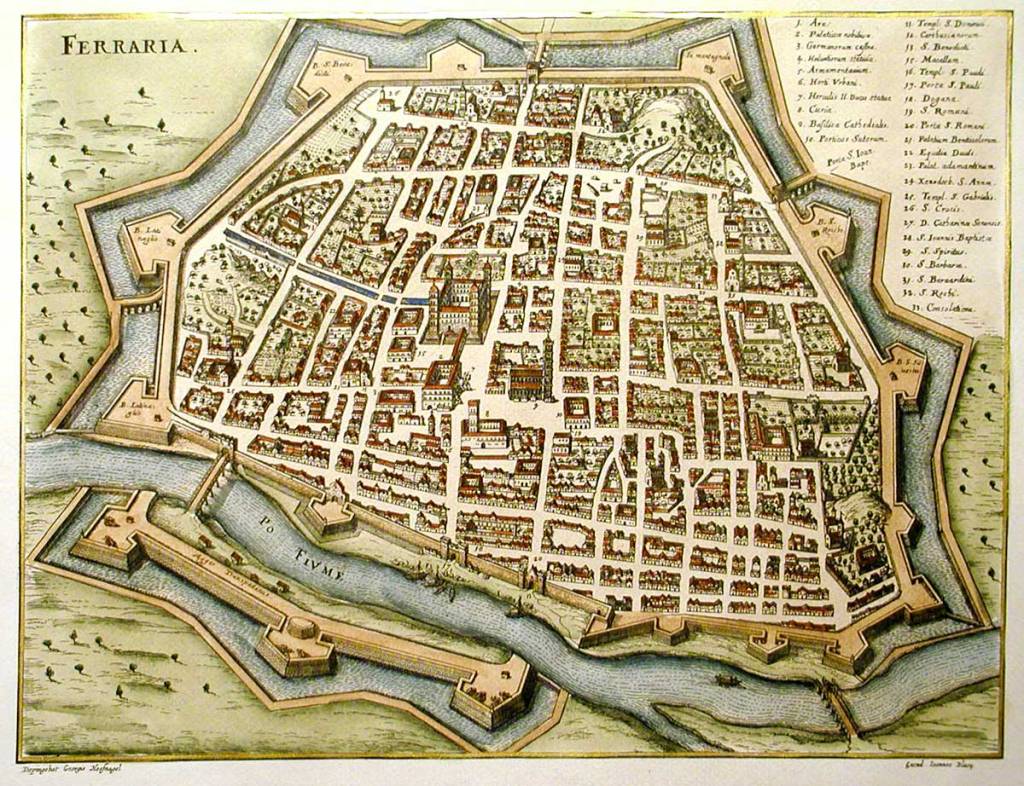

Giorgio Bassani is one of Ferrara’s most famous sons. He was born in Bologna but grew up here. Part of a well-established Jewish community. He went on to become a writer, literary critic, editor and publisher. His book ‘The Garden of the Finzi Contini’ is a romantic semi-autobiographical tale of a young man who falls in love with a young woman. The book is set in Ferrara and describes elegantly and passionately a young man cycling around the walls of the city, playing tennis with his friends and dealing with impending adulthood. When this group of friends is excluded from the local tennis club because they are Jewish, they start to meet at the Finzi Contini residence, where there is a tennis court. The book is set in the 1930s and early 1940s. The backdrop is the Fascist world of Mussolini which fanned the flames of anti-semitism from the 1920s onwards.

As I step from the caretaker’s house into the walled cemetery garden I’m almost blinded by the bright sunlight reflecting off the white marble stones. The cemetery is deserted, I am the only visitor. The atmosphere is melancholy, brooding. Tombstones and memorials lean, abandoned in the long grass, giving a slightly neglected air. I walk carefully along the path, wary of the sleeping inhabitants, both beneath and above the ground. Ahead of me there is a chapel in classical Roman style. I push the metal door open, it creaks loudly on its hinges, to reveal an empty space, dusty, forgotten.

On the wall there is a plaque ‘Polvere sei e alla polvere tornerai’ in other words ‘You are dust and you will return to dust’. I immediately reflect on life’s transience. Our inevitable mortality. I’m stood in the family mausoleum of the Finzi-Contini family. I’m almost overwhelmed by the emotion and tragedy of this tranquil place. Very few of Ferrara’s Jewish community survived the war. Most were shipped off to concentration camps in Eastern Europe. In fact in a postscript to his novel Bassani writes that the Finzi-Contini family were taken to Milan in late 1943. From there they were taken by train to Germany. Never to return. The Finzi-Contini tomb in the cemetery contains none of the family members that Giorgio Bassani knew as a boy, except Alberto, a son who died of cancer in 1942.

The Second World War was fought from 1939 to 1945. It is ironic and painful to consider that the Jewish population in Ferrara survived until the end of 1943. At about the same time that the Allied Forces were landing at Salerno in Southern Italy the Jewish community in Ferrara was being rounded up and imprisoned. I find it almost overwhelming to realise that they ‘almost’ survived. But of course ‘almost’ is not good enough. The impact of these events on Giorgio Bassani’s life was profound and informed his writing career. Much of his work focused on Ferrara and the countryside of Emilia Romagna. He wrote with a lightness of touch that conveyed the charm and the joy of life in this smart, wealthy little city and the magnificent surrounding countryside. Even at a time when war was imminent, people went about their lives, studying, working, falling in love.

I start to think about the Jewish migrants who arrived in Italy over the centuries, often fleeing war and persecution. In medieval times many Jews arrived from the east and settled in Venice, Ancona, Rimini and the other Adriatic seaports of Italy. In fact the term ‘ghetto’ originated in Venice where an old foundry became the first Jewish neighbourhood in Europe and where the term ‘ghetto’ was first used. Gettare in Italian means to throw, as in create or throw an iron coin, a possible derivation of the word ‘ghetto’. Others suggest that a ‘small town’ or area in Italian is known as a ‘borghetto’ so perhaps ‘ghetto’ comes from a combination of ‘gettare’ and ‘borghetto’. The new migrants would often take the name of their place of entry as their family name in an attempt to appear more local. In the cemetery at Ferrara there are many tombs with the family name Ancona, engraved on the headstone. There are still Jewish families in Italy that have the name of the town where their family members first arrived in Italy centuries ago, Ancona, Palermo and Pesaro are just a few.

By the 16th century Jewish communities were very well established in Italy. They tended to live a segregated existence in a specific part of the city. In Ferrara you can still see the Jewish Quarter with its narrow streets and crowded housing. They were often subjected to a curfew, as in Venice where the gates of the ‘ghetto’ were closed and locked at night and opened again each morning. Although I remind myself that by the 20th century the Jewish community in Ferrara was fully integrated into local society. They were professional people; lawyers, doctors, architects, business owners and academics.

I meander along the pathways of the cemetery, treading gingerly, respectfully on the earth. Ahead of me is a tall brick wall I decide to walk to it and trace the boundary of this garden burial ground. I stop frequently to read, or try to read, an inscription. I peer into gloomy stone interiors, filled with spiders, dead leaves and vegetation. Ahead of me I see a new memorial stone with a wreath, it is green, red and white – the colours of the Italian flag. It is a relatively new memorial to Giorgio Bassani dedicated in 2003. The memorial is made of bronze, said to integrate sky and earth. The base of the plaque is reminiscent of the keys of a type writer, whilst higher up the Hebrew alphabet is visible. The memorial is adjacent to the burial place of Bassani, who died in 2000.

For me, the writer Giorgio Bassani recorded a time in Ferrara’s history that was unique and exceptional. He describes characters that lived vibrantly and passionately. Almost certainly unaware of their ultimate fate. The lasting and outstanding memory for me of the Jewish Cemetery in Ferrara has to be the tombs and memorials to the countless Jewish families who used to live in this city. The individuals who were deprived of their liberty and finally their lives. Individuals who would have no descendants to tend their graves. Individuals dependent on writers like Giorgio Bassani to record their legacy, in words, so that they would not be forgotten.

Notes:

- Giorgio Bassani’s novel ‘The Garden of the Finzi Contini’ was published in 1962

- When I first read the book it had a profound influence on me, to this day I still can’t quite accept the dreadful fate of most of Ferrara’s Jewish population in the closing years of the Second World War. I keep thinking, they nearly made it.

- The novel was made into a film in 1970. I mention the Finzi Contini film in this article: The Leopard and other exceptional Italian Films…

- In 1970 Vittorio de Sica made the book into a film. You can see a trailer for the film here: A short trailer for the film ‘Il Giardino dei Finzi Contini’

- Tim Parks wrote a review of ‘The Garden of the Finzi-Contini’ in the New York Review of Books – July, 2005 it is worth a read.Tim Park’s review

- The City of Ferrara is truly magical – probably my favourite small city in Italy – you can read more about it here: Ferrara – a perfect, small city in Italy

- For a short piece of ‘magical realism’ check out La Custode – The Guardian

- During a long and influential career, Giorgio Bassani was also responsible for publishing ‘Il Gattopardo’ when he was a director at Feltrinelli. This is a fabulous novel written by Giuseppe Tomasi de Lampedusa. It is an epic tale of a Sicilian family and the changes that took place during the unification of Italy in the 19th century. The novel was published post-humously in 1958. I’ve written about ‘Il Gattopardo’ too: The Leopard and other exceptional Italian Films…

- In 2018 the city of Ferrara opened the MEIS Museum celebrating Jewish Culture in Italy. MEIS stands for ‘Museo Nazionale dell’Ebraismo Italiano e della Shoah’

- It is a fascinating museum and well worth a visit: www.meisweb.it

- Ferrara is a smart, small city, an hour south-west of Venice. Go if you possibly can and discover it.

- Updated: 08-11-2018

- Updated 27-12-2021

John – thank you – as always for your lovely comments. I think the grammatical error was Lucy and I – instead of Lucy and me. Andrew had already pointed it out to me!! However in true wifely fashion I had ignored his helpful input! Really glad you enjoyed the article. J x

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for writing this Janet. I’ve just watched the film, and it’s helpful to read some of the context. What a shocking tragedy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for writing this Janet. I’ve just watched the film, and it’s helpful to read some of the context. What a shocking tragedy.

LikeLike

Wonderful story. I was in Ferrara recently. It is a gorgeous city but I was there for only a short time.

LikeLike

Totally fascinating. You’ve sent me back to the book which I read many years ago (also saw the film), but so much I’d forgotten and, of course, I didn’t know all the information you;ve given.

LikeLike