The brilliant red and sparkling white of the Swiss flags dance in the mountain breeze. Today is the National Day of Switzerland. I’m standing in a room with a wooden ceiling, timber-panelled walls and long, refectory-style tables. There are place settings for at least one hundred people. White linen tablecloths and red napkins, sparkling silver cutlery and porcelain plates, all positioned with a watch-maker’s precision. The windows at the end of the hall have been thrown open to allow the mountain air to pour in, energising and oxygenating the interior. The room is prepared for a great feast. Tiny posies of Alpine flowers decorate each table, gentians, edelweiss, cowslips and primula. Delicate scents infuse the air.

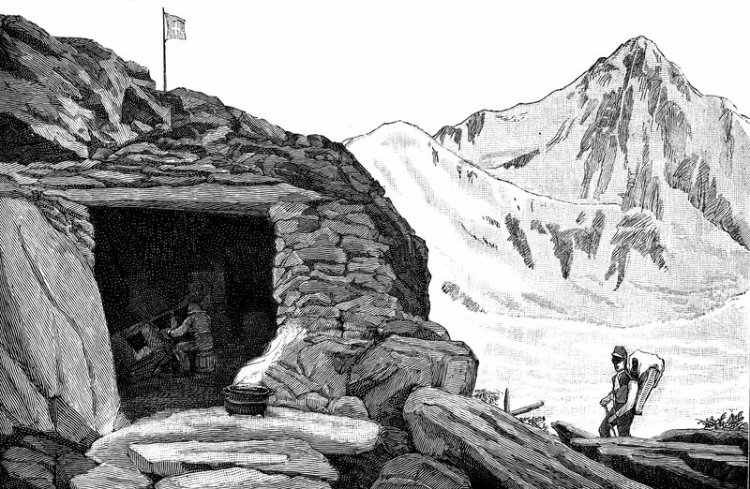

Outside I can see the spectacular Grimselsee, a vast man-made lake. Beyond is the narrow road snaking up the mountain to the Grimsel Pass. At 2165 metres above sea level this is one of the high alpine passes. The mountains around me are ancient granites and schists, millions of years old. The mountain tops here are covered in snow all year round. The Grimsel Pass is right on the border between two Swiss Cantons, Berne to the north and Valais to the south. As the crow flies we are just a few miles from Italy. Here in the Canton of Berne[1] and neighbouring Valais[2] there are several passes that effectively link Northern and Southern Europe. This is the watershed of the Alps, just a mile or so away is the Aar Glacier and slightly to the east is the Rhone Glacier reached via the Furka Pass. The Furka was popular with Victorian tourists heading to see the source of the Rhone. This area has attracted visitors and mountain lovers for two hundred years. The Aar Glacier is the largest in Europe – it was here that Louis Agassiz a Swiss scientist and fossil expert came to develop his theory of glaciation. He built a hut on the glacier in the 1830s for annual ‘summer’ observations of the behaviour of the ice. Agassiz’s hut survived several seasons before being destroyed by the movement of the ice. Nick-named by the locals the ‘Hotel de Neuchatel’[3] the hut provided Agassiz with shelter and the opportunity to make scientific observations. It was jokingly called ‘Hotel de Neuchatel’ because it was a little hut built on the glacier – and the crazy scientist from Neuchatel who spent his summers there observing the ice was regarded as slightly mad by the people of the area.

They say that it rains every single day at the Grimsel, this may not be true, but it certainly seems like it. The day I arrived I drove up the mountainside in driving rain and swirling mist. The higher I climbed the worse the weather became and the poorer the visibility. I missed the turning for the Grimsel Hospiz[4] and had to double back, proceeding at a snail’s pace, peering through the windscreen. Eventually I saw a small sign directing me to the hotel. I turned onto a narrow causeway that links the ‘hospiz’ with the main road. The causeway was built in the 1930s and runs along the top of a gigantic dam. It is single-track, massive, grey, gothic. I felt nervous and uneasy, creeping forward at about 5 kilometers an hour. I was able to make out a flickering light ahead of me, and then another, and another. A line of street lamps illuminated the road in front of me. Beyond I could just make out the mass of a granite building looming through the mist. I had reached my destination.

The Grimsel Hospiz is situated at 1980 metres above sea level. It is an amazing building in an exceptional location. Perched on a rocky outcrop over-looking the Grimselsee. The ‘hospiz’ has a fascinating history. There has been a lodging place here since the 12th century. It was originally built to accommodate weary travellers. By the Victorian period it was a popular departure point for tourists visiting the Rhone and Aar Glaciers. By the 1920s it was one of the few alpine lodgings with electricity. About five years ago the local power company refurbished it and re-opened it as a very comfortable overnight stop. Today it is a very well-run and extremely Swiss hotel. The floors are polished stone, the restaurant is in typical Alpine style. The bedrooms are wonderful, modern and stylish with sleek bathrooms. Sheets are high quality cotton, towels are white and fluffy. It is heavenly. There is a sitting room with books and a fireplace. A fellow guest is snoring gently in a reclining arm chair. He has definitely made himself at home. One wall is floor to ceiling windows, which must offer incredible views of the mountains and lakes around. Unfortunately the weather prevents me from seeing anything. However, I’m here in the mountains, it is magnificent, the weather is brooding. As the light fades I head for dinner in the timber-clad dining room. It’s a fixed menu, delicious food and a really good wine list. As the wind continues to howl outside I decide on an early night. I resolve to get up at day-break and keep my fingers crossed for some better weather.

The next morning around dawn the mist continues to swirl around the ‘hospiz’ building. I am determined to experience the landscape around me. I put on all my clothes (I hadn’t expected such wild weather in mid-summer). I step out of the comfort and warmth of the interior into the fresh, invigorating air. I walk briskly back and forth hoping for a glimpse, just a glimpse of the dramatic landscape that surrounds me. Impatiently I begin to decipher a sign in German, it takes a while because I don’t speak German, it explains the weather statistics that are collected at this spot. Rain-fall, humidity levels, wind speed and direction are all recorded here.

Unexpectedly, a voice in the mist startles me and makes me jump. A bearded gentleman fully kitted out in expensive walker’s garb, proper boots, sensible waterproof anorak and hat is standing in front of me. He looks, slightly contemptuously at my chaotic, amateur outfit of leggings, several tee shirts and a light-weight waterproof jacket. I haven’t even got a hat. He introduces himself as Mr Payne, I introduce myself as Janet. He explains that he is a serious walker and is waiting for a break in the weather before he continues up to the base of the Aar Glacier. He also explains carefully and in great detail that a walker in this high-alpine environment should be properly equipped at all times. Again he glances disapprovingly at my clothing. I’m beginning to feel just a little uncomfortable. The combination of the wild weather, foggy conditions and this earnest gentleman’s presence makes a casual early morning wander far too intense.

Just behind the ‘hospiz’ there is a self-operated cable car. It takes you further up the valley and on a clear day offers amazing views. Mr Payne tells me that he doesn’t really feel like using it today. I must admit in this weather I can’t say I blame him. I visualize being in the cable car, surrounded by fog, alone, no point of reference…….You have to hand it to KWO – the Swiss Power Company that is responsible for both the cable car and generating vast amounts of electricity in this valley – they really are trying hard to make the whole area a tourist attraction. Mr Payne wanders off grumbling, he has the air of a man who is about to make a nuisance of himself at the hotel reception desk. I am relieved to be alone again and free to think my own thoughts. I’d love to head up to the Aar Glacier myself, I’ve always loved the story of Louis Agassiz and his ‘observation hut’. I consider the weather yet again – but it really isn’t very promising. I decide to stroll across the causeway in the mist – perhaps I’ll be able to glimpse the lake and the monumental dam beneath my feet.

When the idea of ice ages invaded the drawing rooms of Victorian Britain it created a new kind of tourism. Hundreds of middle class Brits headed for the Alps, intent on enjoying the mountain air, hiking in the hills and walking on the glaciers. Less adventurous types would collect butterflies or mountain flowers. This tourist boom arrived in Switzerland in the 1860s. Visitors arrived first by carriage and later by train. The Swiss responded to this arrival of visitors by constructing mountain railways and mountain hotels with great vigour. At the nearby Furka Pass is the village of Gletsch (which means glacier in German) and The Hotel Glacier du Rhone. In the 19th century the hotel’s location was dangerously close to the nose of the Rhone Glacier. Visitors loved the proximity of the glacier and the frisson of danger that this engendered.

The Victorians were obsessed by the Alps and the health-giving properties of fresh mountain air. As Robert Macfarlane so eloquently explains in his book ‘Mountains of the Mind’[5]the British effectively invented the idea of ‘holidaying in the mountains’ and were largely responsible for the development of many Swiss and French mountain resorts. Chamonix and St Moritz are perfect examples of Alpine resorts developed by and predominantly for the British. Numerous travellers headed to the Alps. John Murray, the famous publisher of travel guides advised in 1838 that, ‘the best panorama of the Grimsel and neighbouring peaks and glaciers may be seen from the top of the Seidelhorn at 8634 feet above sea level’.[6] Sir Arthur Conan Doyle spent a holiday in Lucerne in the 1890s and took a trip to Meiringen where later his famous detective Sherlock Holmes and his enemy Moriarty would fall to their deaths from the Reichenbach Falls in ‘The Final Problem’. In 1902 Gertrude Bell the intrepid female traveller wrote home describing the inhospitable weather she encountered at The Grimsel.

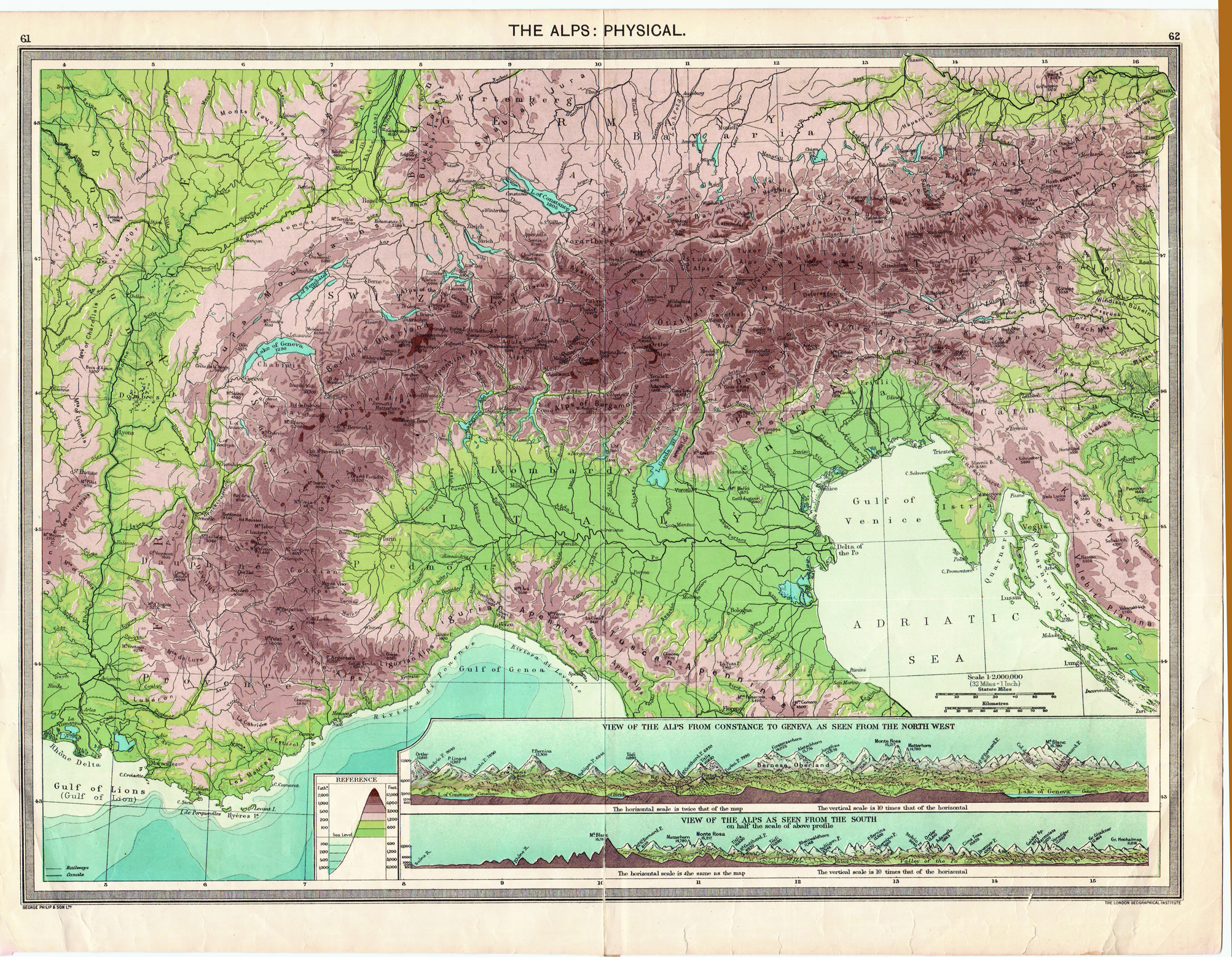

If you look at a relief map of Europe – the Alps appear as a huge physical barrier separating France and Germany to the north from Italy and Greece to the south. The High Alps have fascinated me for years. This is effectively the water-shed of Europe. Here at the Grimsel you are in striking distance of not one but two massive glaciers. In the next valley is the Rhone Glacier and a few hundred meters above is the Aar Glacier, comprising the Unter Aar and Ober Aar branches. Here in this inhospitable high altitude region you have not one but two of the largest and most important glaciers in Europe. The Alps are the generator of our water supply. Millions of gallons of water flow down these mountains every year, from glaciers that cover the highest slopes and have done for thousands of years. Since the 1920s this abundant water supply has allowed the production of hydro-electric power[7]. In the Grimsel Pass area there is a series of vast reservoirs supplying water and electricity to huge parts of Switzerland. Water management and power generation here is in the hands of the Swiss KWO Company. Since the 1980s the company has invested heavily in underground turbines, pipes and pumps. The consequence of this is that the visitor sees a series of lakes, several dams and some electricity pylons but gone are the ugly generator units and unsightly over-ground pipes and pumps.

I see the Grimsel and the work of the KWO as an interesting example of man’s impact on the environment. There is no doubt that this area of barren, isolated, craggy peaks has been profoundly influenced by man’s activities. However if I were to ask the question, has this been done efficiently and sensitively and with an eye for the aesthetics of the region – I’d have to say yes. In the last twenty years the KWO has been on a massive charm offensive. They’ve invested heavily in accommodation for visitors, started tours of their facilities and refurbished the Grimsel Hospiz.

You can tour the Crystal Cave, visit the underground tunnels, take cable cars high up the mountain side and visit the Reichenbach Falls. For serious geologists there is even the ‘Grimsel Test Site’[8].

But even the might of the KWO can’t control the weather. As I stumble across the Causeway in the swirling mist, desperate for a glimpse, just a glimpse of the curve of the dam and the majesty of the lake the clouds suddenly part. A chink of blue sky appears and the visibility improves. I can see, really I can see the landscape around me and it is wonderful. I trot excitedly back to the ‘hospiz’ where the view from the terrace is spectacular.The Grimselsee stretches far into the distance. It is magical, breath-taking. From above I suddenly become aware of a delicate scent, the smell of alpine flowers. I look up and see the open windows of the hall decked out for the Swiss National Day. Next year, I say to myself, next year, I will be here for the Swiss National Day.

- Words and layout – Janet Simmonds / April 2015

- I visited the Grimsel Hospiz on 31st July, 2014

- I liked it so much I returned in August 2015. A unique and exceptional place. I’ve been back several times since.

- To contact the hotel directly www.grimselwelt.ch

- For more on The Alps – Switzerland, France and Austria then I suggest you have a look at:

- A short piece on Lake Lucerne

- Glaciers and Mountains

- Crossing the Alps in May Fun and Games at the Brenner Pass

Footnotes:

- [1] Berne is one of the oldest cantons in the Swiss Confederacy – joining in 1353

- [2] Valais is one of the newer cantons becoming part of Switzerland in 1815.

- [3] The name of the hut was a joke referring to Agassiz as a native of Neuchatel (French-speaking Switzerland).

- [4] ‘Hospiz’ is a word commonly used in the Alps to refer to an overnight resting place, offering bed and food. Originally run by religious orders.

- [5] Macfarlane, Robert (2003) ‘Mountains of the Mind’. A beautifully written history of mountains and their importance in the human psyche.

- [6] John Murray (1838) – A handbook for travellers in Switzerland, Alps of Savoy and Piedmont. This guide book was so popular it was re-printed 18 times. All Victorian travellers had a copy in their hand luggage.

- [7] Hydro-electric power (HEP) is the generation of electricity from water. It is a clean and renewable energy source.

- [8] The GTS is an underground test site available for scientists and geologists interested in investigating rock strength and characteristics under extreme pressure. There is also a facility for researching storage of radio-active materials.

- The Grimselwelt web site has an excellent range of suggested hikes in the area. Hikes in the Grimsel

- Updated: 20-12-17 / 20-01-18 / 04-04-2018 / 07-07-19

Interesting. However, just for information (I can provide details and illustrations), the present hospiz is NOT on the site of the original (which was a ‘spittel’ or hospital), but higher up. The original site is now under water, as the reservoir covered it in 1929. Whether that one had electricity (you write “in the 1920s”) or not I don’t know.

LikeLike

Thank you Stephan for taking the time to send a message. Your insight is so useful. Of course KWO view the Grimsel Hospiz as a gigantic marketing opportunity for their electricity generating company. I have found no mention (in english) of the actual flooding activity in the valleys when the reservoirs were created. Best wishes, Janet S

LikeLike