When a group of young people met up at the Church of Santa Maria Novella in the centre of Florence, towards the end of the fourteenth century, the talk was of the plague that ravaged the city. The friends decided to escape the threat of death and take up residence in a beautiful villa set in an exquisite, flower-filled garden. There were ten of them, seven young women and three young men. To pass the time they decided to tell stories. Each person told one tale a day over a ten day period. One hundred tales in total. The subject of the tales included love and romance, humour, greed, kindness dishonesty and treachery. Collectively the tales were a comment on the human condition of the time.

Each day one of the group was elected king or queen for the day, and that person would chose a subject around which the group would weave their stories. The idea of a small group of beautiful, young people, escaping the plague and passing the time telling stories has fascinated artists and writers for generations. The author was Italian humanist Giovanni Boccaccio, and the book was called ‘The Decameron’. Whilst the stories are mostly fictional, Boccaccio was hugely influenced by the plague, known as The Black Death, that brought devastation to the city of Florence from 1348-1350. It was exactly at this time that Boccaccio wrote his book.

The Decameron, was written in every day Italian, instead of the Latin more common in books at that time. It is thought to have influenced Chaucer, when he wrote The Canterbury Tales and Shakespeare when he was writing ‘All’s well that ends well’ several centuries later. Boccaccio himself had been influenced by Dante, who wrote the Divine Comedy from 1308-1320 about his own journey through the after life. The Divine Comedy, was divided into the key sections of Purgatory, Paradise and Inferno. Dante recorded in graphic detail the traumas and torture that sinful souls would suffer in the ‘Inferno’ if they had led greedy and morally corrupt lives. In ‘The Decameron’ Boccaccio created his own ‘Human Comedy’ with his tales of fun and deceit, humour and joy, love and loss.

The idea of a group of seven young women and three young men fleeing the plague-ridden city of Florence, to set up home in a deserted villa in the hills for a two week period is an intoxicating one. Not only do the group put the immediate threat of the plague at a distance from them, but they also create the space and time to converse and to chat. Boccaccio’s brilliant theme of ten stories for ten days enables the reader to experience and hear many different voices and to absorb different ideas and philosophies from a range of view points. Each of the ten characters takes turn to be King or Queen of the company for a day. The leader chooses the theme of the stories for that day, for example, the power of fortune, the idea of human will, love stories and romances, tragedy and happiness, the concept of good and evil, and perhaps the tricks that people play on each other and even themselves. One character in the group, Dioneo, can tell any tale he wishes, he is the last speaker of the day. Some historians believe that Dioneo is Boccaccio himself. The basic plots of the various stories cover many concerns of the day; greedy and corrupt churchmen, social hierarchies, old money versus new money, the perils of every day life, how to live and love when disease threatens our daily habits and our way of life.

It is striking that almost seven hundred years after writing ‘The Decameron’ Boccaccio’s work is so appropriate and applicable to our lives today. A previously unknown illness circles the globe in just a few months, the speed of infection and rapidly increasing numbers of cases has quite literally paralysed our daily lives. A background dialogue of fear, uncertainty and concern permeates every aspect of our existence. Just like the Black Death of the 14th century there is no end in sight. And yet the incidence of plague historically is a regular phenomenon. The City of Venice, dominated trade in the Eastern Mediterranean for hundreds of years. On three occasions the plague arrived in the city, delivering disease and death to the population. In the 1340s ‘La Peste’ was characterised as a fatal lung infection. In the 1570s the plague came back to Venice, carried by rats. When it finally receded, grateful Venetians commissioned architect Andrea Palladio to build the ‘Redentore’ Church, as a thank you to God for delivering them from the plague. Every July there is a special feast day celebrating the feast of the ‘Redentore’ a poignant reminder to us that Venice survived the plague. Plague doctors and their masked faces and beaky noses are familiar to us as carnival characters. In the days of the plague, the carnival mask had a serious purpose, it kept the stench of rotting corpses at a distance and it reduced the spread of the disease by distancing the wearer from infected individuals. The beak of the mask was often filled with herbs; thyme, rosemary, oregano and marjoram to alleviate pustulant odours.

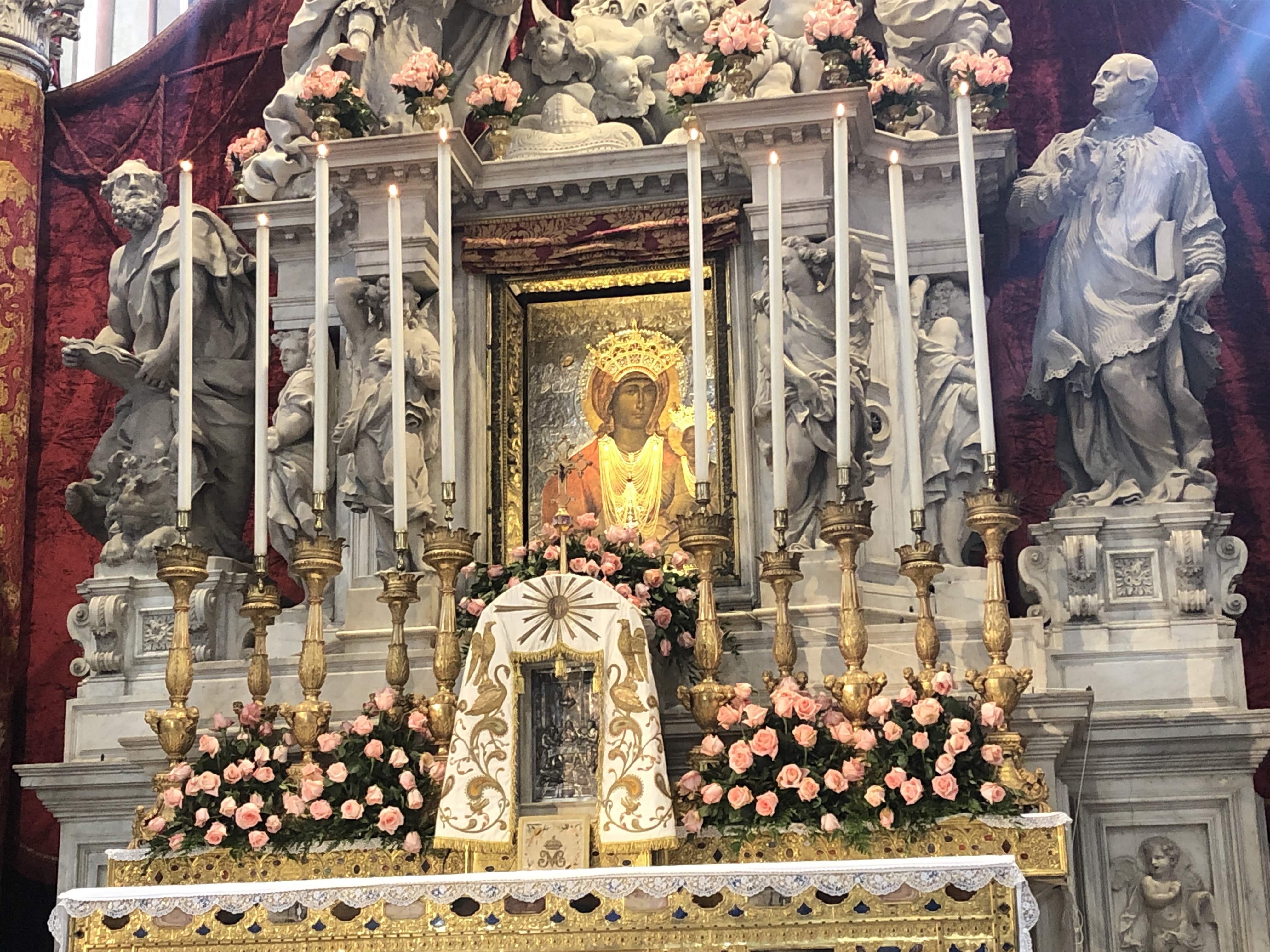

In the 1630s the plague was back again in Venice. It destroyed more than a third of the population. Once again the city leaders decided to build a church to celebrate Venice’s survival. This time it was the Basilica of Santa Maria della Salute, a Baroque masterpiece by Baldassare Longhena. Santa Maria della Salute means ‘St Mary of Good Health’ a very appropriate title for a religious festival that celebrates ‘salute’ or well-being. In November last year, I was present at the ‘Festa della Salute’ in Venice, along with most Venetians. It was only days after the high water flooding that had caused great damage to Venice and the islands of the lagoon. The church was filled with people; families, couples, children, pensioners, all bearing candles. The interior of the church was beautifully decorated with pink roses. The atmosphere was joyful and grateful – even though just days before, Venice had been inundated by water. I was overcome with respect and admiration for the Venetians; tough and resilient, clever and hard-working, kind and funny. If any group of people know how to deal with adversity then it is the Venetians.

Writers and artists are often inspired by difficult times and unsettling events. Fear of the unknown causes us to recalibrate what really matters to us and what can be disregarded as frivolous nonsense. When Boccaccio’s protagonists retreated to their rural villa in Tuscany they were escaping disease, but they were also escaping the routine and mundanity of every day life. The fresh air that they could breathe on the hillside was sweeter, fresher, more gentle than the putrid, infected air of the city. Their distance from the city of Florence also gave them a new perspective. The stories they told however, were often brutal, cruel, even miserable. As Sandro Botticelli demonstrates in this painting (below) of 1482, inspired by the 8th story, on the 5th day of the Decameron, the course of life and true love rarely runs smoothly. The painting shows an elaborate banquet held in the pinewoods near Ravenna. The party is rudely interrupted by the ghostly presence of a young woman fated to be chased by a knight and hounds for failing to love her admirer (the young man in red tights). This terrible event is repeated daily, in the style of a Greek Myth. A reminder to us all that we should never, ever trust or communicate with a man in red tights, however shapely his physique, because he absolutely cannot be trusted and might well subject us to eternal damnation.

Even in the last century there have been several examples of epidemics causing havoc and disruption to the normal order of things. Thomas Mann’s novella ‘Death in Venice’ published in 1912, is set on the Lido of Venice and features a great writer suffering writer’s block and the effects of advancing years. Meanwhile the city of Venice succumbs to an outbreak of cholera that brings both writer and city to its knees. Perhaps it is the unexpected and unforeseen nature of these contagious and deadly diseases that we find so unsettling. Unpredictable and difficult to control, they are a threat to us all, regardless of age, gender or social position. Such events force us to question our usual assumptions about our lives. Assumptions of peace, order and tranquility, the right to travel anywhere and everywhere. A set of privileges that our parents and grand-parents could never have taken for granted. A set of assumptions that we should now reconsider very carefully indeed with a new found modesty and appreciation.

Notes:

1/ Andre Spicer at The Cass Business School in London suggests that The Decameron gives us a possible blueprint to survive these troubled times. https://www.newstatesman.com/2020/03/coronavirus-survive-italy-wellbeing-stories-decameron

2/ A pilgrimage from Chartres to Canterbury: Chartres to Canterbury – A Pilgrimage

3/ For me – the ideal dose of sanity comes from a trip to a really traditional library, probably my favourite is Gladstone’s Library, Hawarden, North Wales. For me it is a ‘Sanatorium for the Mind’ /2015/07/20/sanatorium-for-the-mind-gladstones-library-wales/

4/ For other articles on Italy, The Alps, British Isles, Life and Travel, explore further: www.greyhoundtrainers.com

5/ Special thanks to my friend Mr John Eaton for his helpful comments.

16th March 2020 / 25th March, 2020

Beautiful post! Della Salute is such an iconic church. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love the Waterhouse painting.

The other two – full of corseted ladies in the latest 19C fashions – are hilarious!

LikeLiked by 1 person