Stormy weather this season offers the perfect unsettling sensation to this year’s biennale visitors. The theme of this year’s Biennale in Venice is ‘Stranieri ovunque’ which translates as strangers or foreigners everywhere. In fact ‘stranieri ovunque’ seems to include the weather. It was rainy and quite cold in Northern Italy for the whole of the month of May. Now the arrival of summer heralds hot, humid weather and crazy thunderstorms.

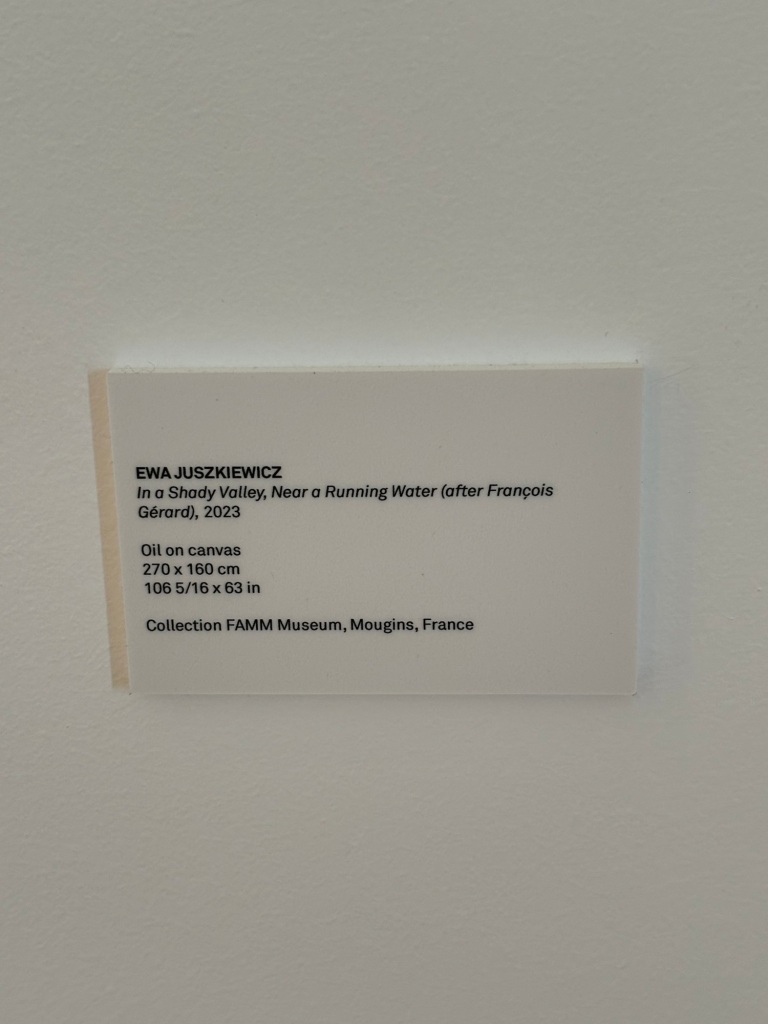

As I was sheltering from yet another downpour of rain, I spotted a poster for a small exhibition in Palazzo Cavanis on the Zattere. Wandering inside I came across a curious interpretation of portraiture. A series of richly painted portraits all with their faces covered. What’s in a face you might ask, well not much if artist Ewa Juszkiewicz is to be believed.The impact of these faceless portraits was disturbing and surreal. They made me feel uneasy and at the same time fascinated by the structure of the paintings. The pose of the subjects, the elegance of the clothing and the vibrant colours of the artist’s pallet.

The artist is Paris-based Ewa Juszkiewicz and this capsule exhibition is a collateral event of this year’s Biennale and is on show at Palazzo Cavanis, Dorsoduro until November, 2024

Once again the artist is Ewa Juszkiewitz – new to me and based in Warsaw. She paints extraordinary pictures combining traditional portraits with still life arrangements rather than a face. Here show in Venice runs through until 30 September, 2024 as a Venice Biennale collateral event. Juszkiewicz is a truly exceptional painter; colour, texture, detail are sublime. She describes herself as a surrealist which makes me think of Leonora Carrington. Her paintings stay with you, they haunt you, they make you think – in a bizarre and interesting way. I’m reminded of painter Elizabeth Vigee Le Brun in terms of portrait style or Pompeo Batoni. The artist describes her motivation in these words, ‘I wish to tell a new tale and create my own language: ambiguous, dense, natural, and organic’.

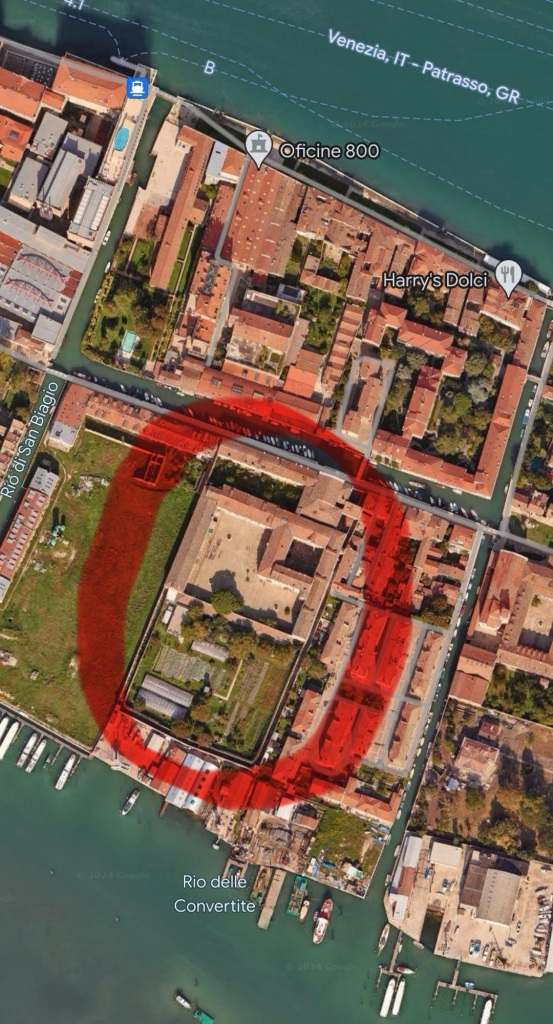

Meanwhile just across the water – less than 10 minutes by boat from Palazzo Cavanis is the Giudecca Island. Here on Giudecca is the Women’s Prison ‘Casa di Reclusione Femminile di Venezia’. The prison is located on a small canal and is generally ignored by the majority of visitors to the island. The doors are locked, windows are barred and the inmates are excluded from the outside world. There is no escape.

This year, for the first time, the prison is the location of an art exhibition as part of the Biennale. The event is sponsored by the ‘Santa Sede’ (The Holy See) in other words The Vatican City. When I first heard about this venture I was deeply sceptical. What exactly was The Vatican doing financing an art event in a Women’s Prison? Had the Roman Catholic Church not done enough over the years to interfere with women’s rights? I decided I needed to discover more and see the whole thing with my own eyes, which, funnily enough is the title of the exhibition: ‘Con i miei occhi’

Consequently in May, 2024 I found myself at the entrance to the Women’s Prison and this is what I wrote: The Women’s Prison, Venice

A little context – The Biennale Art installation at the Women’s Prison features a variety of artists, including Claire Fontaine (an artistic collective based in Palermo), who are responsible for the powerful slogan ‘siamo con voi nella notte’ this translates as, ‘We are with you in the night’ and is a neon banner that dominates the usually bare brick wall of the exercise yard, deep within the prison complex. There’s also an eye with a diagonal line through it positioned below one of the watch towers, also by Claire Fontaine. The unseeing eye is quite disturbing it excludes us from viewing, implying forbidden or not available.

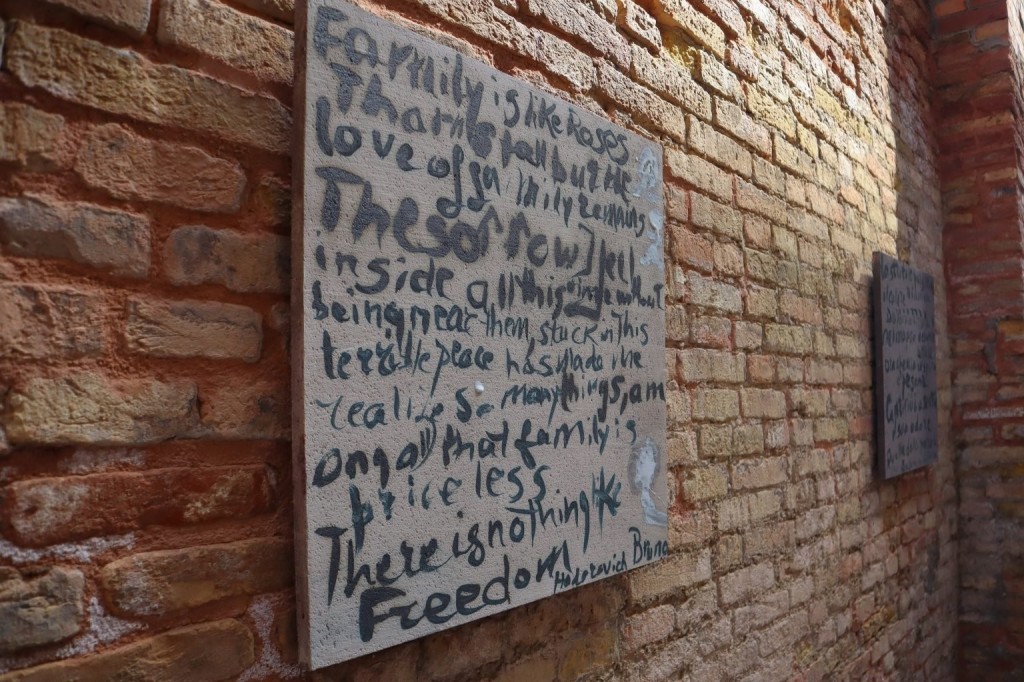

Other artists who have participated in the prison installations include Simone Fatale, whose volcanic stone slabs line the walls of the entry corridor. Each stone filled with the prisoners own words. These make for tear-jerking reading, words such as ‘family is priceless’ ‘sorrow’ ‘this terrible place’ and lastly ‘there is nothing like freedom’ makes the viewer wonder what this is all about. How can the imprisonment of these women, removed from their families and children, possibly benefit anyone? Only in a tiny minority of cases can such incarceration be justified.

Prison Exercise Yard, photo: Luca Bruno (left) and Simone Fattal’s volcanic stones (right) – photo Naomi Rea

Visitors to the prison, during the Biennale, are guided through the complex by two prisoners. The day I visited our guides were articulate, quietly confident and thoroughly engaging. We weren’t permitted to ask them personal questions, we had to restrict our comments to the art. However this rule fell apart when we entered a room where photographs of the women’s children were on display. One of our guides pointed out her own son, whose photo had been taken four years earlier, the implication was that she hadn’t seen him since. The same woman pointed out the only window in the prison that doesn’t have bars, it’s an internal window that looks out on to the garden where inmates grow vegetables and fruit. The produce from the garden is sold on a rickety wooden table, outside the prison entrance, every thursday morning by local volunteers.

Important – The Women’s Prison houses about 60 inmates, for whom there are only locked doors. Our tour continues with a black and white film starring Zoe Saldana (she was in Avatar), she’s not a prisoner! The rest of the cast are prisoners. The short film shows a woman on her release day, saying her goodbyes to her friends who will remain inside. She collects her meagre belongings, makes her way through the various locked doors of the prison and gives a final wave to her fellow prisoners, before finally emerging into the outside world, startled by the bright sunlight.

The chapel dates from 15th century. It houses a material installation by Brazilian artist Sonia Gomes. Photo: Marco Cremascoli

Technically there are lots of opportunities to work within the prison. There’s a productive vegetable garden which prisoners tend and the harvest is used in the prison and sold to local people too.

There’s also a tailor’s workshop in the prison (Sarto in Italian) and prisoners are able to make dresses, skirts, jackets and so on. There’s even a shop in Venice that sells the clothing made in the prison. I’ve taken clients there – the garments are beautiful, handmade and in fabulous colours. The quality of the cloth is excellent too. I really don’t know how much the tailoring unit helps the prisoners (financially or emotionally). As recently as April of this year I was in the shop with a small group of friends and a number of purchases were made. People feel good about supporting the prison and the inmates.

However it doesn’t matter how many rehabilitation opportunities are available, none of these activities replaces freedom, the freedom that has been taken from these individuals.

As Abraham Lincoln said,

“Those who deny freedom to others deserve it not for themselves.

“For to be free is not merely to cast off one’s chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others.”

A visit to the Women’s Prison is a ‘percorso’ through life. A journey into our very souls. I emerge from the ‘casa di reclusione’ chastened, grateful (for my freedom) and deeply unsettled. To deny an individual their liberty is a brutal and callous act. Is it ever appropriate?

I’m struggling to believe that it is…..

“Those who deny freedom to others deserve it not for themselves’

Notes:

- I create high quality journeys in Italy – especially Venice, Veneto, Trieste, Marche. All written and curated by me and a small team of dedicated professionals – don’t hesitate to get in touch and do please check out our website: www.grand-tourist.com

- For further reading on Italy, The Alps & Beyond please explore the blog: www.greyhoundtrainers.com

- You can read more about Ewa Juszkiewicz at the Gagosian website: www.gagosian.com

- For more on this year’s Venice Biennale: www.biennale.org

July 2024