The mud flats and islands that make up the footprint of Venice were deposited by rivers, flowing from the Alps to the Adriatic Sea. These rivers started their journey high in the snow-capped mountains of Europe, cascading through gorges and steep valleys before crossing the plains of Northern Italy towards the sea. These rivers are the oxygen of Venice, a source of life, replenishment and renewal. Each water source is unique and vital to the health of Venice and the lagoon.

RIVER BRENTA – Standing on the banks of the Brenta at Dolo I’m transported back in time, almost four centuries in fact. Here an artist called Antonio Canale, better known as Canaletto (little canal) stood and painted. The scene he captured ‘The Mill at Dolo’ remains unchanged to this day. The original painting is in The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford – I booked an appointment to see it last year, on a cold winter’s day in England. It’s not on public display, it’s in storage. What is striking is how little the scene that Canaletto painted has changed in the last 350 years. The Brenta still flows through this little town, where the wooden water wheels turned to generate the power to grind the flour for the local people. And due to a recent local initiative, the mill wheel has been restored and renewed and turns as the Brenta pours vigorously through the millrace.

To control the flow of the Brenta, and to reduce the risk of flooding, a giant lock was built just east of Padova. The river was divided into two streams, one flowing south, out into the sea at Chioggia, the other flowing through a series of locks out into the lagoon of Venice at Fusina. The Brenta at Dolo is part of the canal or naviglio that was a popular location for wealthy Venetian families to build their summer homes. Many of these beautiful historic houses can still be seen. They dot the river banks from Stra where Villa Pisani dominates the waterfront down to Malcontenta where Villa Foscari is perhaps the most perfect and authentic of the Palladian villas.

People have been adapting and changing the river courses in the Veneto region since at least Roman times and probably before that too. Just to the east of Venice, the Roman city of Aquileia had a large, prosperous river port (porto fluviale) consisting of warehouses, quays, loading and unloading areas. All constructed around the Second Century to facilitate trade with Greece, Southern Italy and ports throughout the Eastern Mediterranean. Closer to Venice the town of Altinum, located just inland from the lagoon was a thriving Roman town. Archaeologists have discovered evidence that Altinum exported goods and food stuffs to other parts of the Roman Empire. Goods were taken in small boats to Torcello, one of the islands in the lagoon, transferred onto bigger, sea-going ships and then transported south into the Adriatic. The history of human involvement in the lagoon of Venice and the mainland that surrounds it is a long and complicated one. It is highly likely that the Veneti, the local people who lived here before the Romans arrived were using the lagoon of Venice for fishing and boat building and that small communities existed on Torcello and other islands.

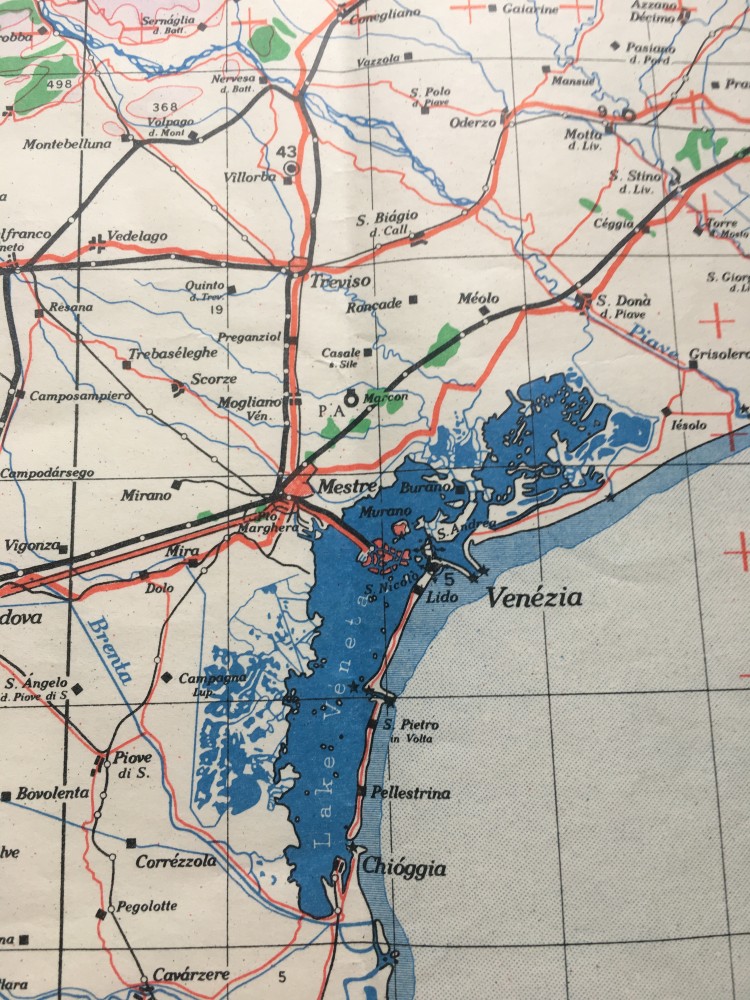

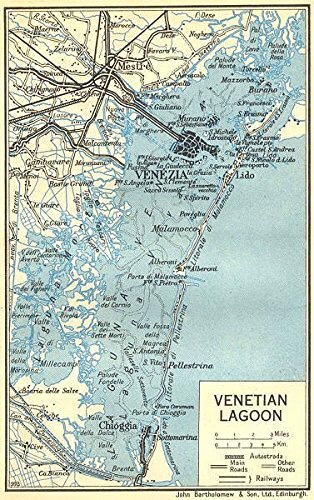

In fact, when you look at a map of the Venetian lagoon, human activity is evident everywhere. You don’t get straight lines in nature, so whenever a waterway is completely straight, you know immediately it is man-made. On the other hand, natural curved shapes are usually natural. A good example is pointed out by Iris Loredana in one of her excellent blog articles, where she explains that the Grand Canal, which runs through Venice, is in fact the former river course of the Brenta. When you look at a map the S shaped curves of the Grand Canal mirror the meanders of a river as it flows out into the open sea. The reason the Grand Canal is this shape is because it was created by the shifting currents and meandering patterns of the River Brenta in the final kilometres before it reached the Adriatic Sea. It is also evidence that Venetians worked with the land formations that they had, for example higher, more solid ground at the Rivo Alto, high bank, which became the district of Venice known as Rialto.

At the northern end of the Venetian Lagoon the River Piave, regarded by Italians as the sacred river of the ‘patria’ because of the terrible loss of life along this river in the First World War, flows out to sea just near the seaside resort of Jesolo. Large stretches of the lower Piave have been straightened and reinforced over the years to control the flow of the river and reduce the risk of flooding. The River Sile flows into the lagoon in moreorless the same area. At Caposile, head of the Sile the two rivers meet. Managing this watery environment has been a challenge over the centuries. In the 1920s and 30s huge irrigation and drainage projects were initiated by the Mussolini government. Draining the marshes created large, new areas of fertile soil, ideal for farming. It also reduced the mosquito population and therefore the incidences of malaria. Although in certain areas of the lagoon the mosquitoes do seem to have made a bit of a come back in recent years.

The complicated interaction between the rivers, lagoon and open sea doesn’t end when the fresh water of the Piave, Sile, Brenta or Dese decant into the Venetian Lagoon. In fact, if anything it becomes even trickier to understand. In certain peripheral areas of the lagoon, especially near Torcello, vast areas of wetland create ideal habitats for all types of birds. The water here tends to be quite fresh tending towards brackish. The salt content is not high. However as one moves towards the sea, the river water blends with the tidal waters of the Adriatic and the salt content of the water increases. So the water of the lagoon changes as it makes its way to the open sea, from fresh water or brackish water in the northerly reaches to seawater adjacent to the Lido and Pellestrina. Interestingly the colour of the water changes too, from a blue-grey colour adjacent to the landward side of the lagoon to a blue-green colour closer to the Adriatic. This will also be caused by the reflection of light from the sandy sediment deposited on the bed of the lagoon as the rivers finally make their way out into the open sea.

As a frequent visitor to Venice I always scan the lagoon for evidence of water quality. In my opinion the quality of the water in the lagoon is good. For example, many peripheral areas of the lagoon have significant numbers of fishermen, making their living from harvesting the lagoon. If you drive along the Piave or Sile you’ll see large fishing nets suspended above the river, drying in the sun. Decent fish numbers means properly oxygenated, good quality water. Visually the water in the lagoon is clean, luminous and free from obvious pollutants. On the principle ‘fondamente‘ in Venice, marble steps are covered in seaweed and mollusc populations. As filter feeders mussels and clams cannot live in polluted waters. So this is a good sign of the healthy nature of the water. The old myth that Venice smells is no longer true, as drainage and sanitation has been improved. Just beyond the airport there’s a huge nature reserve, a large wetland area designed to attract numerous bird species – ornithologists are already recording increased numbers of sightings and activity levels in this liminal area between land and sea.

For centuries people living in the Veneto region, both in the lagoon and on ‘terra ferma’ have performed a balancing act, managing their local primary resource of water. On the one hand the risk of flooding from the numerous rivers in the region needs to be reduced, on the other hand drainage patterns must not be interrupted too much. It’s a very subtle and delicate balance. The situation is complicated further by Venice’s global attraction as a tourist destination. As Lorenzo Quinn, sculptor and artist, commented recently, ‘Everyone who comes to Venice wants part of it’ and he’s right. This city has a global appeal. So the challenge is to manage this exceptional watery environment, with respect for nature and local habitats so that we can all appreciate this unique ecosystem. There has to be space for all living things; people, plants, animals and a profound and sensitive respect for our natural world. In this way we can all benefit both now and in the future.

KEY POINTS – The mud flats and islands that make up the footprint of Venice were deposited by rivers, flowing from the Alps to the Adriatic Sea. These rivers started their journey high in the snow-capped mountains of Europe, cascading through gorges and steep valleys before crossing the plains of Northern Italy towards the sea. These rivers are the oxygen of Venice, a source of life, replenishment and renewal. Each water source is unique and vital to the health of Venice and the lagoon.

For numerous articles on Venice why not browse this blog further:

- www.greyhoundtrainers.com

- I also recommend Iris Loredana’s fantastic blog: La Venessiana

- On the recent ‘acqua alta’ in Venice – I wrote this article: Acqua Alta – Venice

Updated: 20-11-2019

Further reading on Venice & Lagoon:

Ernest Hemingway, Venetian Lagoon

Torcello – Island of legends – Cipriani, Hemingway, Venice

All from the pen of ‘The Educated Traveller’ masquerading as ‘The Grand Tourist’ providing high quality tour guiding services in Italy, The Alps and Venice! Greyhound Trails Travel

Updated: 12th Jan 2024

6 thoughts on “Venice and the lagoon, a vast natural harbour…”